Friday, December 02, 2026

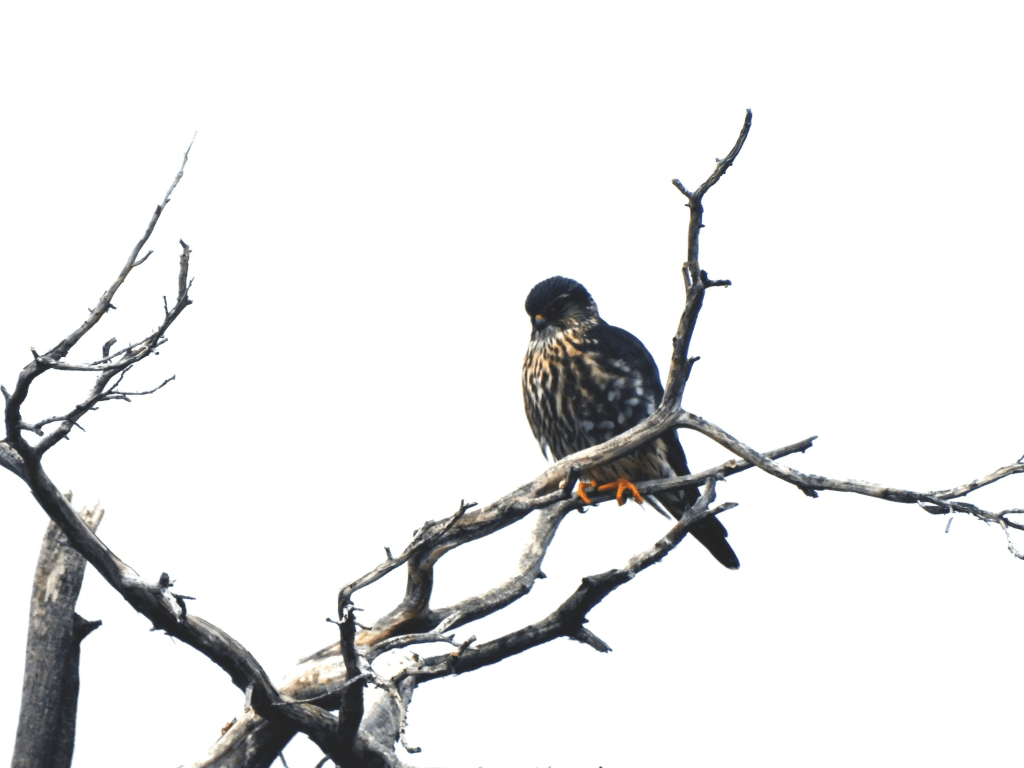

At first, I thought I was photographing a hawk.

That was my quick naming reflex—efficient, tidy, and not particularly curious. Hawk was close enough. But after looking at the image longer, my certainty loosened. I saw the bird’s compact weight. The way it was holding itself—contained, almost coiled. There was the bright grip of its feet against the bare branch. Those visuals weren’t exactly matching a hawk.

I started looking again. This time, not asking what category might this creature of flight belong to? Instead, what did it actually feel like to encounter this bird? The shift mattered, changed my perspective. Simply staying longer with the image made me reevaluate.

I recalled a moment of surprise upon spotting the bird, to see it staring straight down–directly back at me–alert and strong-looking. Remembering that stare and looking more closely at my image made me unsure about a hawk. Searching on my phone revealed something else: a Merlin–a small falcon, perched securely, holding very still, and wintering quietly under Central Oregon’s pale sky.

This correction was about paying attention and resisting the rush to name and move on. Looking again, more closely, did more than refine identification—it deepened the encounter. It made that bird less a specimen and more a presence–a compact, deliberate, Merlin, utterly sufficient to itself.

A small act of correction—caused by the bird’s stare made me realize I wasn’t seeing a hawk at all. That stays with me as another moment of learning. I had misidentified the bird because my first impression was nearly satisfactory. By pausing and correcting, I thought of how often we simply accept our initial impressions, because they arrive quickly and let us move on.

I’m discovering that maturing, or aging, can alter our learned, habitual grabbing for answers.

The urgency to name things immediately loosens over time. Needing to arrive quickly at conclusions—to decide what something is, and what it means, and what it’s for—softens. Something quieter replaces it: patience. Unlike an impatience for resolution—it’s another kind toally, that lets uncertainty linger without causing discomfort.

To me, “looking again” has become a shifting away from haste.

When I was younger and usually employed in complex organizations, decision speed often passed for competence. Quick recognition, quick decisions, quick judgments—all felt necessary. Now, as a retiree, I’m willing to let first impressions revise themselves. I stay with first impressions long enough to let subtleties emerge. Truly, first assumptions can be incomplete.

This Merlin didn’t change. I changed. On looking again and remembering the circumstances, I felt willing to linger with the vision, to give the experience time to clarify itself. As I age, this pausing to look again becomes increasingly familiar. Less “rushings toward certainty” invite better quiet unfoldings.

One of aging’s gifts isn’t sharper vision — it’s longer looking. Less loud insight and more steady attention. Patience is less a virtue of quick performance and more a natural outcome of learning. As we evolved, didn’t we already do enough rushing?

More patience gives time to “the ordinary” (e.g., a cool-looking bird on a wintery branch)—to reveal its particularities. My subjects might not actively be demanding special attention, but increasingly I’m willing to slow down and offer it.

— Diana