Saturday, November 22, 2025

Imagining The Circle

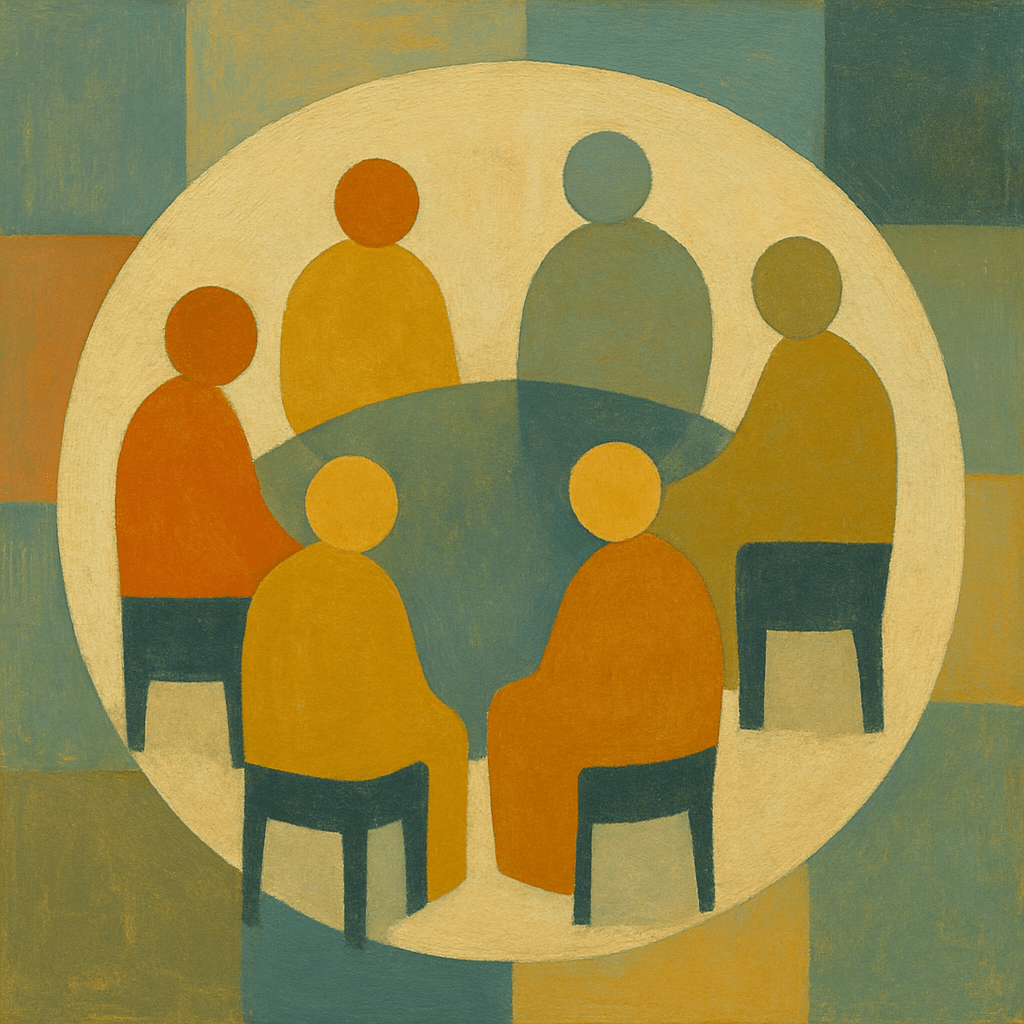

In my mind, the group isn’t large. Maybe six to twelve people—enough for richness, but small.

I’ve written recently that those of us in our 70s, 80s, and 90s may be discovering that we’re living in moments no one could ever have prepared us for. These days, we find ourselves living healthier longer, staying mentally alert longer, and remaining deeply engaged with the world longer—way beyond what earlier generations ever imagined. Our younger society hasn’t yet recognized all the changes affecting its oldest population. These changes are personal, complex, sometimes isolating, and often surprisingly similar among people of advanced ages.

Writing has made me consider such “elderly biological and cultural shifts” more deeply. I’m even imagining what it might “look like” to gather with others also navigating the new territories of aging. I’m not visualizing a formal club or a structured workshop—just a thoughtful, recurring space to talk about our “inner lives of growing older” in today’s world.

What A Group Might Feel Like

In my mind, such a group isn’t large. Maybe six to twelve people—enough for richness, but small enough for real conversation. A circle of chairs, not rows. A living-room feel, not a classroom. Perhaps it would meet monthly or every few weeks, with no obligation beyond showing up and being oneself.

There needn’t be a leader in the traditional sense—it’s more of a shared stewardship. A group that could gently guide itself, the way good conversations naturally do. Meetings might center on topics. One might be the surprise of still feeling young inside. Others might explore purpose, or changing friendships, or the odd friction between staying capable and being treated as fragile.

The group wouldn’t represent therapy, nor serve as a complaint circle. It’d be a place to name what today’s aging really feels like—and to hear others say, “I’ve felt that too.”

This Matters Because

We’re the first aging generation to find that, while living this chapter of life, we’re also having to invent this chapter. We’re the first generation to be alive for decades of healthy years beyond traditional retirement. And we’re the first generation needing to reconcile our longer lives against an outdated cultural script that still imagines “old age” as it looked fifty years ago.

Our task—to pioneer and modernize the aging experience, may feel easier—and richer—when it’s shared.

This is a suggested “conversation circle” of elderly participants—not a way to solve the larger social issues of aging. It could, however, illuminate them, while also offering grounding, connection, humor, and clarity. It could help participants understand ourselves in ways we don’t always get to while navigating the advanced years alone.

For now, it’s just an idea I am sketching—an outline—a possibility. If others feel the same pull, perhaps it will take shape. As with most meaningful things in life, maybe energy will start to gather around it.

For The “Interested Some”

What’s this group about?

It’s a small, recurring conversation circle for people in their 70s, 80s, and 90s who want to talk about the inner experience of aging in today’s world—identity, purpose, vitality, ageism, relationships, curiosity, and what it means to be living longer and healthier than previous generations. (Okay, too, if people in their 60s wish to participate.)

Is this a support group or therapy?

No. It’s not a therapy or counseling group. It’s a thoughtful discussion circle—more like a gathering of peers who want to explore life’s later years with honesty, humor, and insight.

How big will the group be?

Small—ideally 6–12 participants. Big enough for varied perspectives, small enough for everyone to speak and feel comfortable.

Who leads the group?

There is no formal “leader.” The group guides itself. One person may help keep time or open the meeting, but the conversation belongs to everyone.

What kinds of topics will we discuss?

Topics may include:

- staying healthy and active

- experiences with ageism

- identity shifts and reinvention

- loneliness, friendship, connection

- unexpected confidence or creativity

- memories that take on new meaning

- the realities of energy, motivation, and purpose

- navigating losses while also discovering new growth

Every meeting may have a theme, but there will always be room for whatever people bring that day.

How often will the group meet?

Most likely once a month or every few weeks, depending on what the group decides.

Is there a cost or commitment?

No cost. No long-term commitment. Just come when you feel drawn to the conversation.

Do I have to talk?

You’re welcome to speak as much or as little as you wish. Listening is also a valuable form of participation.

What would the atmosphere be like?

Warm, respectful, curious, confidential, and welcoming. A place where no one is judged for aging in their own way. A place where humor is welcome and honesty is valued.

I’m interested and a Central Oregonian; so, what now?

Simply share your name and contact information to let me know you’d like to be included as the idea takes shape. Once enough people express interest, we’ll choose a meeting time and place.

— Diana