Sunday, January 11, 2026

I always used to rely on movies—not just for entertainment, but for guidance, inspiration, and small lessons in “being human.” Throughout my growing-up years, films were a kind of companion.

The early ones—Hollywood standards of the 40s and 50s—taught me about glamour, timing, and emotion, and that stories can move with an almost musical rhythm. Later, I gravitated toward the New Age filmmakers of Italy, England, and the independent Americans who emerged in the ’60s and beyond. The emerging works felt looser, freer, more searching. They offered complexity instead of polish. They lingered in ambiguity. They asked viewers to stay longer, look again, and participate.

Eventually, as with so many things, the growing internet altered my habits. I stopped going to theaters. I became a streamer—at first enthusiastically. Art houses were becoming harder to find, and searching for them was tiresome. Over time, I watched fewer movies and watched less attentively. Eventually, part of myself drifted. One that used to feel essential, that welcomed art as nourishment.

Right now, considering the year ahead, I’ve started noticing that absence. Not dramatically—but more like realizing a room has gone quiet. I miss great movies. I miss the feeling of settling into a seat, lights dimming, a subtle sense that something meaningful might happen. I miss my own alertness, my old curiosity, my willingness to follow a director’s point of view.

I’ve done a little exploring and learned something surprising. There is an art movie house in this Central Oregon city. And “just like that,” something old and familiar stirred in me.

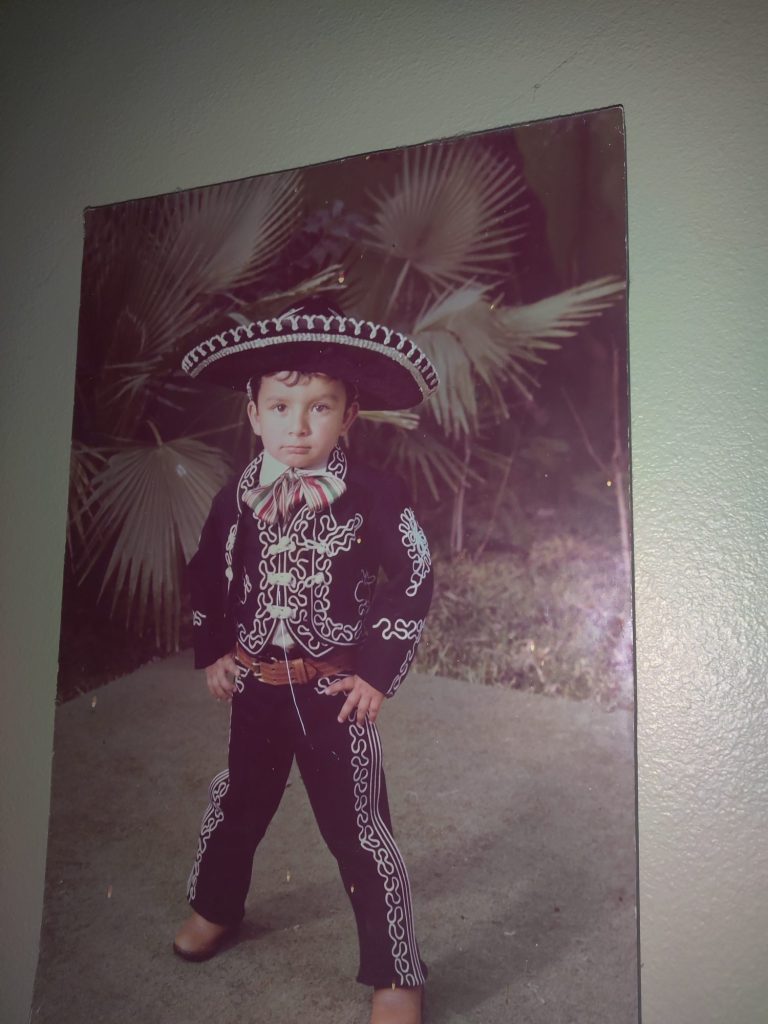

Today’s header photo represents today’s matinee, and I’ll be attending.

Not from nostalgia or needing to reclaim some earlier version of myself. I’m going because sitting inside a darkened room—surrounded by strangers, facing a screen larger than life—once held great purpose for me. And purpose, even if lost for a while, can return in surprising ways. Sometimes renewal begins by doing something small, but true. Something once beloved.

I’ll be watching a very modern American art film. I’ve no idea if it’ll be extraordinary or forgettable. (As a note, this film also might be streaming now, and I’m avoiding that.) Because today I will join a live audience. I will return to a first theatrical experience after many years.

This might renew more than a habit. It might refresh my relationships with attention and imagination. There is a possibility that art can still shift me, nudging me and inviting me into a “different room” than the one I walked into.

Entering this new year has made me think about purpose. Somehow, today’s adventure seems a small re-beginning. I will re-explore a once-significant source of learning. And most importantly, this could be a new beginning.

Later, I’ll know more. About the film itself, and about how it feels to sit, again, in a darkened room with emotional potential. For now, it’s feeling great simply for having decided to go.

— Diana