Sunday, January 18, 2026

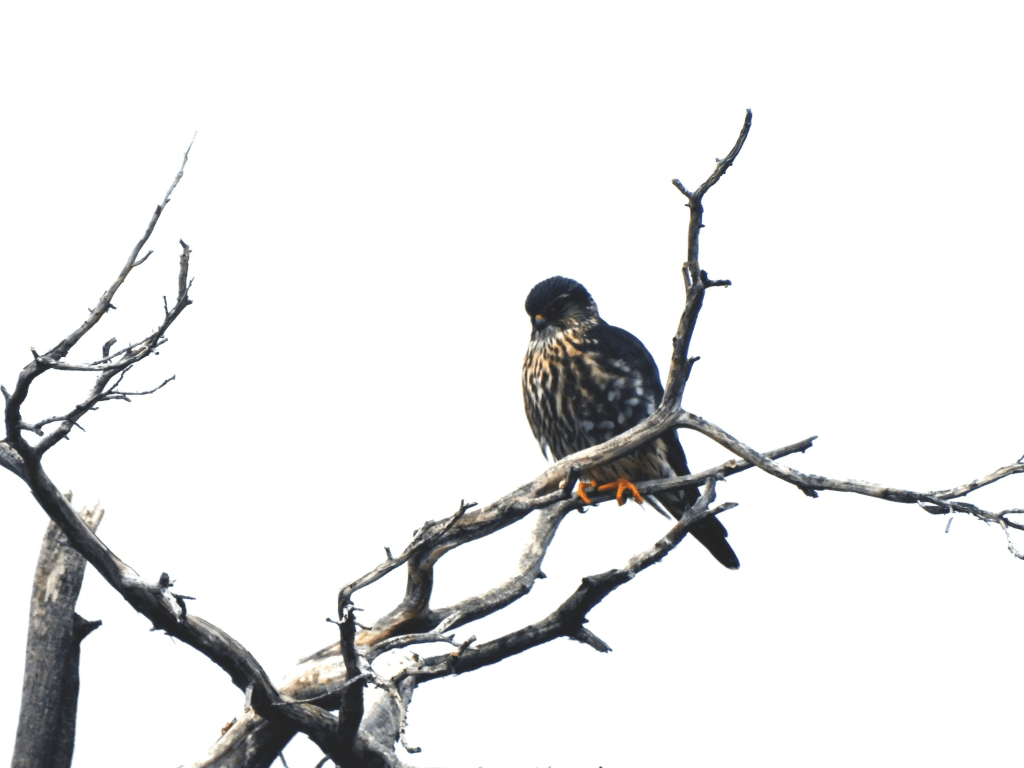

While walking with my camera in a familiar place—a small, local BLM parcel I’ve known for years—I noticed that a bird was perched high in a distant tree. The bird was far away, and my photograph turned out to be, at best, a suggestion—an image lacking crisp markings. Instead of offering a pleasing certainty, it yielded only a shape, a posture, and a presence.

At first glance, the image seemed to reveal the kind of bird it might be. But after trying to identify the type without much luck, I was doubting the possibilities.

This Central Oregon area hosts the wintering birds known as Townsend’s Solitaires—or anyway it used to. In my early years here, I often heard their clear, fluting calls, metallic-sounding, and carrying far across the cold air. In these later years, the Solitaires have seemed fewer—quieter.

Or maybe I’m simply recognizing that it’s easy to miss what doesn’t announce itself.

My first impulse was to identify the bird as a Townsend’s Solitaire—lots of evidence pointed there: its high perch, its stillness, its general outline. But looking again—more closely—didn’t stop my doubts. For instance, a little color spot on the bird’s chest, and a bill that looks long and slightly curved. Those really aren’t Solitaire-like.

Maybe it’s a Hermit Thrush. Thrushes sometimes stay throughout winter—quietly and almost invisibly. A Thrust might be a little rare, but not impossible. Or perhaps it’s a flicker—located far enough away that it appears only slightly so.

The longer I looked, the less certain I felt—and the more interesting I began finding this whole experience.

I often pause to consider something most of us learn early on—it’s a constant desire to name things quickly and be done with it. We’re taught to associate the speed of identification with success. Modern life encourages that habit.

That was my first objective here, too. But taking time to consider the distance of that tree and bird—and later reviewing my imperfect capture—let me start to accept that neither the image nor my memory of that moment offered enough certainty.

That’s when something different occurred to me: this is a photograph that doesn’t need certainty.

Instead, my moments of reflection—and that image itself—seemed to be asking for patience. They were asking for attention—for an observer’s willingness to stay without knowing answers.

I refocused and found that I could view the image differently. I began to sense there wasn’t a need for accurate identification. Already, instead, this image could feel complete. Now, I could see a bird, perched, watching—and entirely undisturbed by my internal debate. Any ambiguities belonged to me alone.

I am posting that photo simply because I like it, and can allow the bird to remain unnamed. Yes, it could have been identified as one type or another. But looking closely and letting myself become involved transformed the experience of seeing. I found another way to understand the whole point of that image’s existence.

This episode was another small learning event. I had seen something at a distance that reminded me of what once felt common; I’d recognized some elements that in general have grown quieter. I decided to allow my thinking-and-feeling processes to be enough—and to legitimize the image.

My work with the camera reminds me constantly of the value in pausing and “looking again.” That practice doesn’t always sharpen answers; sometimes, it serves as a companion, by encouraging a softening of the questions themselves.

— Diana