Saturday. February 21, 2026

Surprised & Delighted—By Rediscovering Geography

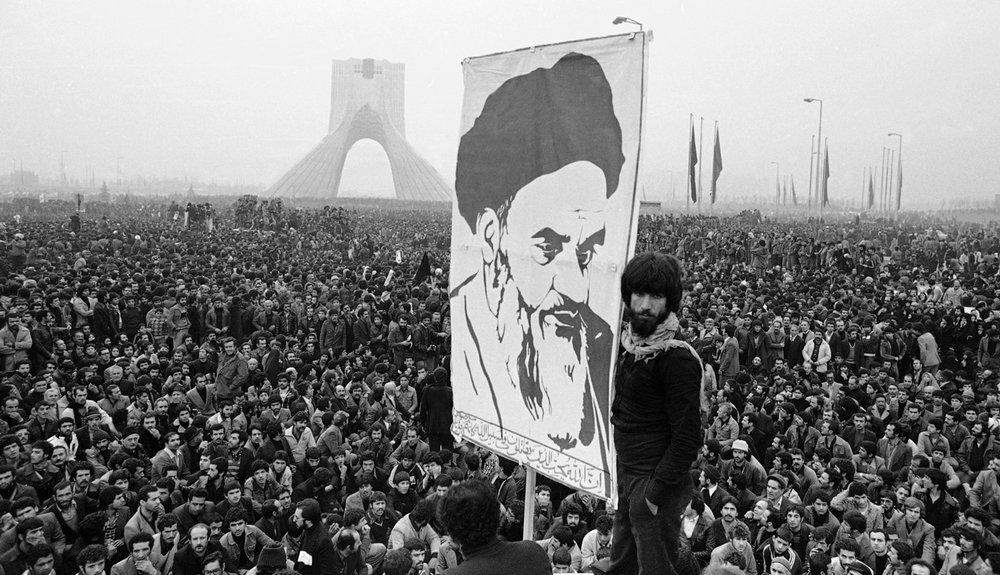

Studying geography is deepening my understanding of world politics by revealing the physical realities that sit beneath international relations. I’ve found that while historical events and charismatic leaders capture our attention, it is the unchanging—or very slowly changing—physical conditions of the Earth that constantly factor into major decisions.

I’m enjoying relearning what I first encountered in grade school. Re-experiencing why a mountain range or a deep-water port clarifies a news story makes my understanding of the world feel more grounded and, importantly, more real.

My most impactful readings so far are Zbigniew Brzeziński’s The Grand Chessboard (1997) and Hal Brands’ The Eurasian Century (2025). Brzeziński sets the geopolitical stage of the 90s, while Brands carries that vision into today’s world. My long-ignored world globe, now dusted off, constantly clarifies texts.

A stack of similarly intelligent books awaits me, and the more I learn, the more I want to share this widened lens.

Why Geography Disappeared

If you are rediscovering geography and are surprised by its relevance, it isn’t because the world changed—it’s our way of seeing it.

Many of us left geography behind in the fifth grade, filed away with pull-down maps and memorized capitals. As curricula shifted toward civics, ideology, and economics, geography faded. Later, the rise of 24-hour streaming news further sidelined our loss by favoring vivid, emotional storytelling over the slow-moving realities of terrain and distance.

Maps vs. Movements

Modern news often favors people over places—focusing on leadership personalities, voter blocs, and moral claims. These stories are intended to capture attention quickly, but they often lack depth.

I have found a few political storytellers who work differently. They explain events by first studying an area’s strategic position, climate, and access. Because geographical conditions move slowly, understanding them requires a level of patience that modern news rhythms rarely allow. We’ve been trained to think of politics through the lens of belief—who is “right” or “wrong”—while the physical world is treated as mere background scenery.

But geography is more than scenery; it’s an active, ongoing force.

The Comfort of Narrative

Geography introduces stubborn realities that can be uncomfortable. Conflicts are often simpler to frame as “bad leaders vs. good values.” That provides senses of clarity and emotional satisfaction.

By contrast, geography focuses on chokepoints, climate, and resource scarcity—complex factors that don’t yield to elections or diplomacy. This reality can feel unsettling because it challenges the comforting notion that history will naturally bend toward a peaceful resolution. It reminds us that persistent conflicts often stem from the Earth’s physical constraints and human struggles to sustain growing populations.

Geography is Returning

Globalization once promised a world where ideas and goods would move seamlessly across borders. But recent years have taught us otherwise. We’ve seen supply chains fracture and energy sources remain unevenly distributed. Technology can compress time, but so far, it cannot eliminate distance.

We are relearning under pressure what earlier generations understood almost intuitively: that ports, islands, and frozen corridors matter. The Earth has unarguable physical conditions, and we are simply the humans debating within them.

Reading the World Again

Returning to geography doesn’t replace my moral concerns; it adds depth to them. I’m slowing down, examining world maps, and asking:

- Where exactly is this happening?

- What physical constraints are shaping these choices?

- Does this mapped position produce courage—or fear?

These questions offset the frustration caused by incomplete news stories. Geography doesn’t belong solely in a child’s classroom; it is a vital lens for refining our understanding of power, conflict, and human behavior. It isn’t a nostalgic return to the past—it is a way to finally see the world we actually live in.

— Diana