Wednesday, December 17, 2025

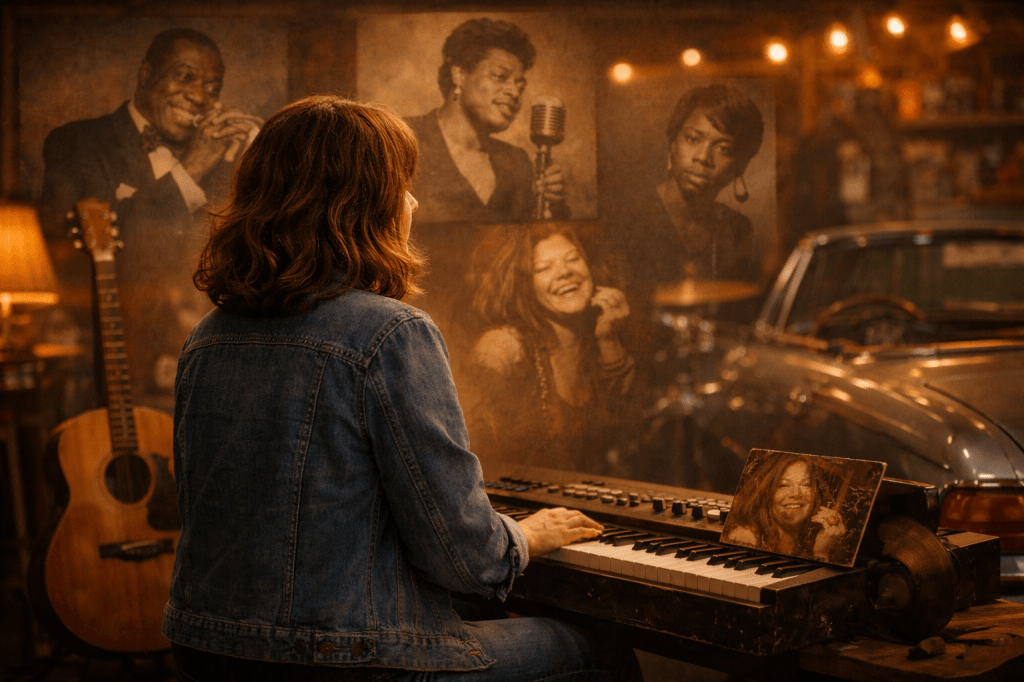

My neighbor—professionally an engineering type—recently introduced me to his garage-based music studio. He and several long-time friends meet there every Friday night to play together. They don’t bother with advance planning; they simply gather and do.

The garage, a crowded but tidy man cave, half houses a skateboard collection, several motorcycles, and a pristine classic BMW convertible. The other half is filled with musical gear—guitars, a professional drum set, a keyboard, seating, and a large TV tuned to YouTube, making music videos instantly accessible. My neighbor says he’s felt intimately connected to music of all genres since he was a little boy.

I sat at the keyboard as he softly strummed a guitar, and we talked about music. I confessed—somewhat sadly—that I’ve fallen out of touch with much of today’s popular music. He queued up a few videos, introducing me to some of it. I was honest and explained that I’m a fan of what I call “the originals.” He understood immediately and shifted the screen to Louis Armstrong, singing alternately through his famous horn and his unmistakable voice. Then came Ella Fitzgerald, gently and passionately interpreting Summertime. We discovered that we share a love for a very modern original as well—Alison Krauss—and listened to her duet with Brad Paisley. Our wandering also touched briefly on cool jazz.

I keep myself too busy to pause and listen as often as I might wish. But after that evening, I revisited my old CD stacks from years of collecting and turned again to YouTube to hear artists I’ve loved for a long time. All of it stirred a familiar question: what is it that makes particular voices call to me so strongly—over equally talented and wildly popular newer artists?

I don’t consciously resist what’s new. Still, I find myself drawn back—almost involuntarily—to certain singers and musicians. Their work feels different, not just in style, but in kind. Especially the voices now gone: Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Nina Simone. Peggy Lee. Édith Piaf. Janis Joplin. Mama Cass. Amy Winehouse. And then there are current figures who still carry that same sense of singularity—Lady Gaga, Robert Plant, Alison Krauss, and a few others.

The word genre doesn’t help much. Jazz, blues, folk, pop, rock—the labels slide off what I’m trying to name. These artists don’t feel as though they belong to categories; instead, the categories seem to bend around them.

The same holds true for certain operatic voices that live vividly in my memory.

Perhaps what my favorite artists share isn’t an era, or even a particular sound. Maybe they share something closer to presence. When they sing—vocally or through an instrument—it feels as though something real is at stake. They aren’t merely performing a song; they seem to carry history, experience, contradiction, and truth all at once.

It’s striking, too, how many of these carrying voices are women’s. Not exclusively, of course—men like Sinatra and Nat King Cole clearly belong in this conversation. But with women, attention so often slides away from the work itself and toward their personal lives, their struggles, their supposed instabilities. Even celebrated women artists have rarely been allowed to remain simply artists. Their inner lives became public property, open to speculation, and too often eclipsed their undeniable musical intelligence.

I’m not going to look for neat answers to complex social realities here, and I’ll leave formal sociology aside. This is a more personal inquiry—an attempt to understand why certain musical patterns never release their hold on me.

Once I begin listening in this way, a much larger story presses in. Many of the voices that move me were shaped by what we now call American music—especially the blues and everything that grew from it—emerging from histories of profound suffering, endurance, and enforced silence. Acknowledging that responsibly requires slowing down, and resisting the urge to compress slavery, survival, and cultural inheritance into a paragraph or a slogan.

I’m not qualified to explain that essential history fully. Instead, I plan to begin here, at the edge of listening.

In future posts, I hope to explore this territory more carefully:

– what originality really sounds like

– why some voices can’t be replicated

– why genre so often fails to describe what moves us most

– and how social history—race, gender, power, visibility—shapes music and how we talk about it

This first post is simply a doorway—an acknowledgment that something important lives here, much like what keeps my neighbor’s Friday-night studio jams alive. And my growing wish to explore it deserves attention rather than speed.

For now, I’ll start listening again.

And I’m inviting you to listen with me.

— Diana