Wednesday, November 12, 2025

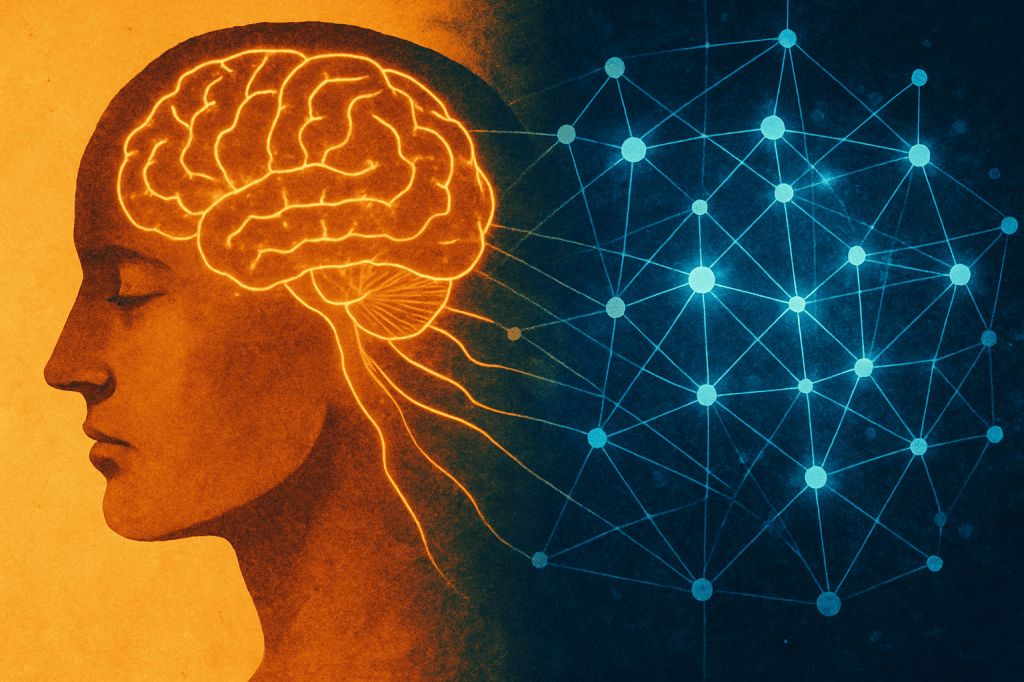

I’m one of billions of AI users curious about why artificial intelligence can seem so humanlike. While working to understand how AI learns, I find myself drawn to a closely related mystery — human emotion. I wonder how—and whether—machine learning and human feelings intersect. So far, here’s what I’ve come to understand.

We humans are becoming more knowledgeable about ourselves by observing the technical processes of teaching AI to “think.” Researchers training the machines are learning from them, too, gaining fresh insights into what being human means.

This deep training of machines to think is reflecting us back to ourselves. The deeper we train, the more feedback we receive. Glimpses into how AI learns offer a new understanding of how we’ve been doing it all along—quietly, efficiently, and with a touch of mystery. That mystery still separates us from the supercomputers we want to emulate us.

It’s an intriguing reversal: AI training is becoming a kind of mirror for human psychology. Modeling AI on the human brain is beginning to decode some of our brain’s most elusive workings. We’re learning, for instance, about a looping relationship between neurons and algorithms—how they both generate profound ideas—and thus reveal more of what it means to learn, imagine, and grow.

AI is showing us that memory isn’t a vault but a living process. Essentially, memory reconstructs. When recalled, memory fragments are rediscovered and then reassembled into something new. Humans recall and reassemble instinctively. For example, we may soften the edges of pain by misremembering certain details, to paint a gentler version of the truth—like artists returning to the same canvas, we repaint our pasts again and again—comforted not by precision but by memory evolution.

AI language models do like us; they build new meaning from old information. They predict the “next possible” word or image, and then create knowledge through probability rather than imagination—and without fear. Humans, too, are prediction-makers, but with one difference: curiosity. We project futures, blend ideas, and dare to believe in “what ifs.” The daring keeps our minds alive.

In teaching machines empathy, we’re discovering something psychologists have long known—that emotion is intelligence. Feelings are not the opposites of logic but are extensions of it. Each emotion is a data point, which helps us interpret what we perceive. Understanding emotional depth reveals, in a kind of wisdom, a refined ability to predict, but with heart.

Even as we age, our brains are capable of change. They reshape themselves through new habits, perspectives, and stories. The AI world calls this continual learning. In human life, we call it resilience. It’s what allows us to adapt, to grow, and to keep the essence of who we are.

AI, for all its precision, still misses something essential—the human advantage of having a heart. Our heart is a living pulse that connects knowledge with caring. Human intelligence, unlike AI, is embodied. It sweats, grieves, laughs, and ages.

The mind’s true elegance lies in its fragility—its humor, its willingness to evolve. Machines can help us visualize the shape of our thoughts, but only humans possess the heartbeat behind them.

Perhaps the most poignant lesson in teaching machines to learn is what they’re teaching us to remember:

the preciousness of awareness, of feeling, and of knowing that we can keep growing.

— Diana