Monday, June 30, 2025

Years ago, long before I imagined a life in Central Oregon or the daily ritual of writing blogs, I worked in a world so classified I couldn’t even discuss my job with friends. Lately, I’ve found myself reflecting on those details—my small but precise role during the early development of the B-2 bomber.

I served as the lead negotiator for a section of the B-2, responsible for negotiating costs and understanding the construction intricacies of my assigned area. That work pushed me deep into technical territory, whether I felt ready for it or not. My focus was on a particular part of the wing. Only later did I fully appreciate how closely my work was tied to the company’s and the nation’s ambitious vision.

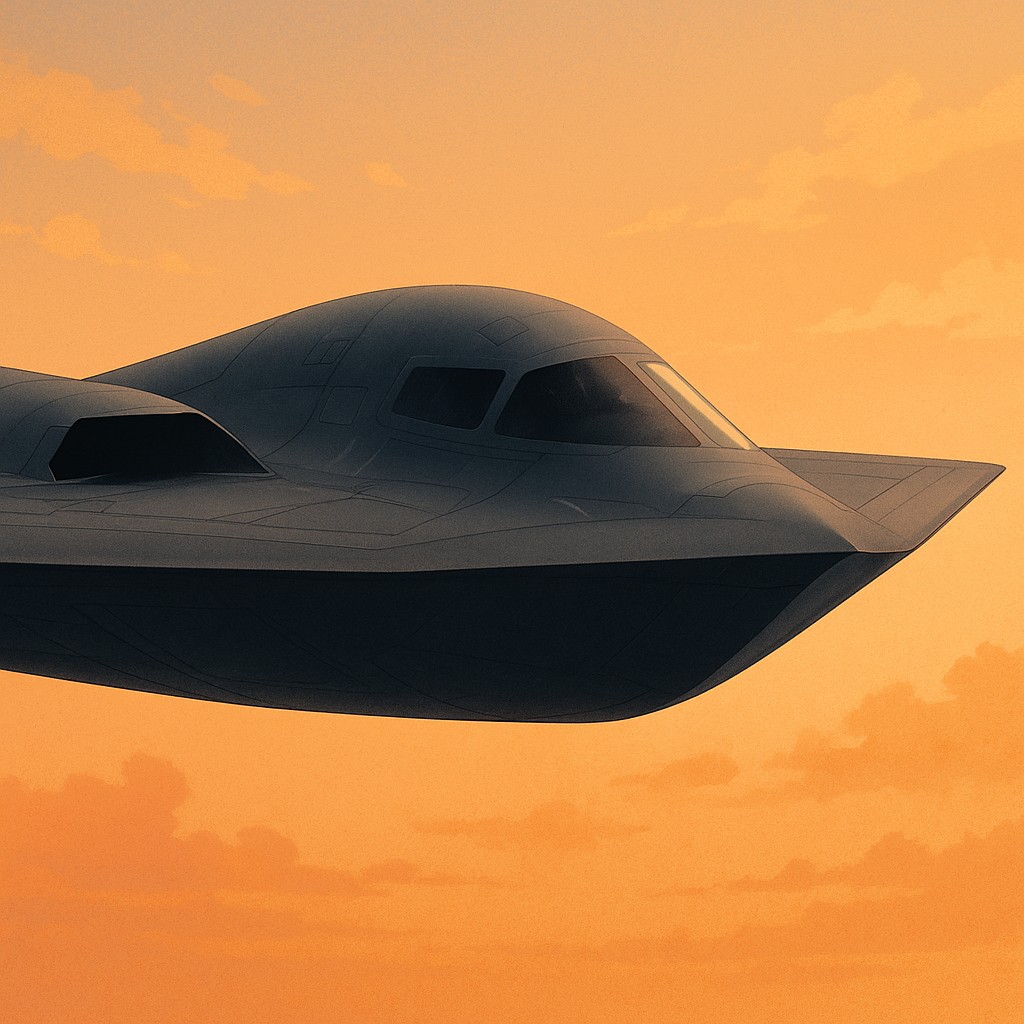

Unlike conventional aircraft with a fuselage and protruding wings, the B-2 was designed as a “flying wing.” That changed everything, including how we talked about it. I recall that we often referred to my section as a “leading wing,” which, in hindsight, is a bit of a misnomer. In a flying wing, every part is forward-facing, structurally critical, aerodynamically sensitive, layered with radar-absorbing materials, fuel compartments, and stealth design features. There is no separate wing area that sticks out; the entire aircraft is the wing.

And there I was—a non-technical civilian—tasked with negotiating costs for a vital section. I sat across from contractors, flanked by my team of engineers, as we discussed pricing that had to align with strict budgets while justifying the necessity and feasibility of every element. These were intense conversations, involving components stamped with a national security imprint. Every dollar needed a clear, defensible rationale. More than once, we joked that maybe this whole thing we were helping to build existed only on paper—a purely theoretical concept.

Much later, we were all invited to witness the first rollout of a completed B-2. I stood in a crowd of employees buzzing with anticipation. We each knew our own “assigned parts,” but only the designers and top officials knew the entire aircraft design. Someone near me quipped that when the hangar doors opened, there might be nothing at all—that the bomber was just a myth. Given the secrecy and fragmented way we’d each touched the project, it almost seemed possible.

Then the hangar doors began to part.

Out of deep shadow, something black, angular, and breathtaking slowly rolled. The aircraft emerged bit by bit—majestic yet alien-looking, unlike anything we’d ever seen. It moved forward with a kind of eerie grace into the light, and the crowd fell completely silent. Then, quietly, tears welled up. Years of effort, meetings, debates, and pages of paperwork had culminated in this astonishing reality. A wing that could fly.

I often forget to include that experience among the formative chapters of my life. But seeing recent images of B-2s soaring through the sky, flanked by fighter jets, brought it all back. That made me want to recapture it here.

Dear friends: Sometimes the small fragments we handle—negotiations, line items, a section of structure—turn out to be part of something far bigger. Sometimes, even airborne.—Diana

That is a very cool story!

LikeLike

This is wonderful – thank you ! Did you know my aunt, Katherine Applegate Keeler Dussaq, was a WASP in WWII? Kate

>

LikeLike